PTSD

**CAUTION** - if you have a personal history of trauma or have experienced a war or conflict situation, you may find this article distressing. Please read it at a time when you have someone around who can support you.

This article traces the development of the term 'PTSD'. Trauma has always been with us, but the concept of PTSD began after World War One. Treatments slowly developed and today there are many avenues of help. Most recently, with the conflict in Ukraine, PTSD has been in the news again. War is traumatic, ongoing PTSD can sometimes be the result - but help is at hand. This article outlines the more medical and psychological sources of help - other articles in this collection (search our site for 'trauma') explain how to support someone who has experienced trauma.

This video on our Youtube channel contains much the same content as the article below but please note that it was filmed prior to the Ukraine conflict.

It all started with a war...

I live a few hundred metres from this place, Craighouse, which used to be called Craig House Hospital. Between the years of 1916 and 1914 there was a unit here dealing with what we first thought of as 'Shell Shock' and later came to understand as PTSD.

It was overseen by a chap called Colonel William Rivers and today, in Edinburgh, the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Centre is called the Rivers Centre. 'Shell Shock' wasn't really something that was well understood. It is something we first recognised in the Crimea and the Boer Wars when heavy artillery started to be used, though of course people will have had similar symptoms to some degree right back through history. The combination of the shell explosion and the loud noises made people think it was some sort of physical impact on the brain from the explosion.

However, what became clear over time was that it was not so much a physical but an emotional or mental impact. That sudden rush of adrenaline that came from being put in situations that were life-changing and indeed brain-changing - was transformative in extremely negative ways that people were not prepared for.

Two of the people who received treatment at Craighouse were the poets Wilfred Owen and Sigfried Sassoon. Here are two extracts of their work: two deeply sad poems about the horrors of war and the ultimate consequences it has. They confronted head on what the popular conception of war was - a glory, a parade, a chance to shine for one's country - and brought home the gritty reality that war is never pleasant and that any victory is at best a mixed one.

Siegfried Sassoon

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

Wilfred Owen

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

Of children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: "Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori."

“Dulce et decorum est - Pro patria mori” means “it is right and glorious to die for one's country.” I think what he's arguing is that actually there never was such a great untruth told. War is not pretty, it's not glorious, and we are now beginning to understand more and more about the psychological consequences of war and similar traumas.

Two Types of Trauma

There have been changes overtime in terms of how we think about trauma, and one of the things to understand is the difference between what sometimes is called type 1 and Type 2 trauma. This excellent article from the charity MIND gives lots of information.

Type 1 is the original description of PTSD that occurs after a single incident. It could be an explosion. It could be a natural disaster. It could be war. It could be a car crash. It could be a one-off sexual assault or similar event. This results in the classic ‘triad’ of PTSD symptoms:

-

Flashbacks to the event (or nightmares about it) - when it feels like the event is happening again in real time, even though the person is safe and the incident is in the past.

-

Avoidance of the place where it happened and related places

-

Hyperarousal – the fight-flight-fright adrenalin response

Then there is Type 2, which is usually associated with childhood trauma of a variety of types, quite often ongoing and long duration. We sometimes use the phrase 'complex PTSD' which describes both the triad of PTSD symptoms, but also some of the developmental and interpersonal relationship difficulties that that can occur when someone experiences something that is very traumatic as a child or over a long period of time.

Something similar that we've come to understand more about recently is what people call 'vicarious' trauma, or secondary trauma. This is when you see trauma being done to someone else, and that has an effect on you. You can begin to experience flashbacks about it, even though it didn't happen to you, but because you feel responsible somehow. This explains part of what was going on with Black Lives Matter and the Sarah Everard case - people who were quite some distance from it began to experience symptoms related to trauma and guilt.

It's almost as though we have inbuilt ethical framework in our heads, which is that good people SHOULD have good outcomes if they work hard. We know in our heads that the maths doesn't always work out like that, but we assume in our hearts that it does and then, when something happens that deeply challenges us, we have this sense of moral injury. In this situation, therapies like CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) don’t address this moral injury and can even make things worse if the person thinks they are the one who needs to be fixed. Instead, the therapist ALSO needs to deal with questions around justice and acceptance.

Trauma vs Stress

At what point does stress become traumatic? I hope I'm not being too blunt in saying that the word ‘trauma’ has been used an awful lot. In the pandemic, did people on intensive care units develop full blown PTSD, or was it instead severe stress without the PTSD? It’s complex, of course! And that is before you consider if a current stress is coming on top of predisposing factors like childhood adversity or other causes of chronic stress. However it is important to make a distinction because PTSD treatments are designed to help process unprocessed and stuck traumatic memories, whereas the "treatment" for extreme stress is not to focus on the person as much but to change the environment and reduce the stress. This is why there has been such a focus on staff wellbeing, compassion and kindness to each other in the NHS.

What we are finding out however is that chronic stress is bad for you in and of itself – causing changes in the brain that can predispose us to problems later on. One of the best ways to prevent full-blown PTSD is to reduce overall stress levels and develop what is called ‘resilience’. Chronic stress means chronically high levels of the hormone cortisol. Lower stress allows us to cope better with the trauma when it comes.

A key component of resilience is having a personal faith. If you look in the PTSD literature, one of the things you find in terms of major protective factors for PTSD is having a faith or spiritual belief. It gives us a different perspective. It gives us a framework for dealing with these moral injuries. It helps us stand back from the stress that's happening to us because we are aware of the eternal perspective. It brings a faith community to help when we are struggling.

There can also be an element of depression mixed in with PTSD. One reason for this is that people with PTSD can often have had fairly good mental health prior to the trauma so assume they should just spring back to full health. So when this doesn't occur, as well as the flashbacks, avoidance and hyperarousal, there is self-blame and self-reproach. “Why can't I snap out of this? I should be able to get over this! How come I'm being affected by this and others aren’t?” This depression needs to be acknowledged and addressed alongside the trauma itself.

Treatment

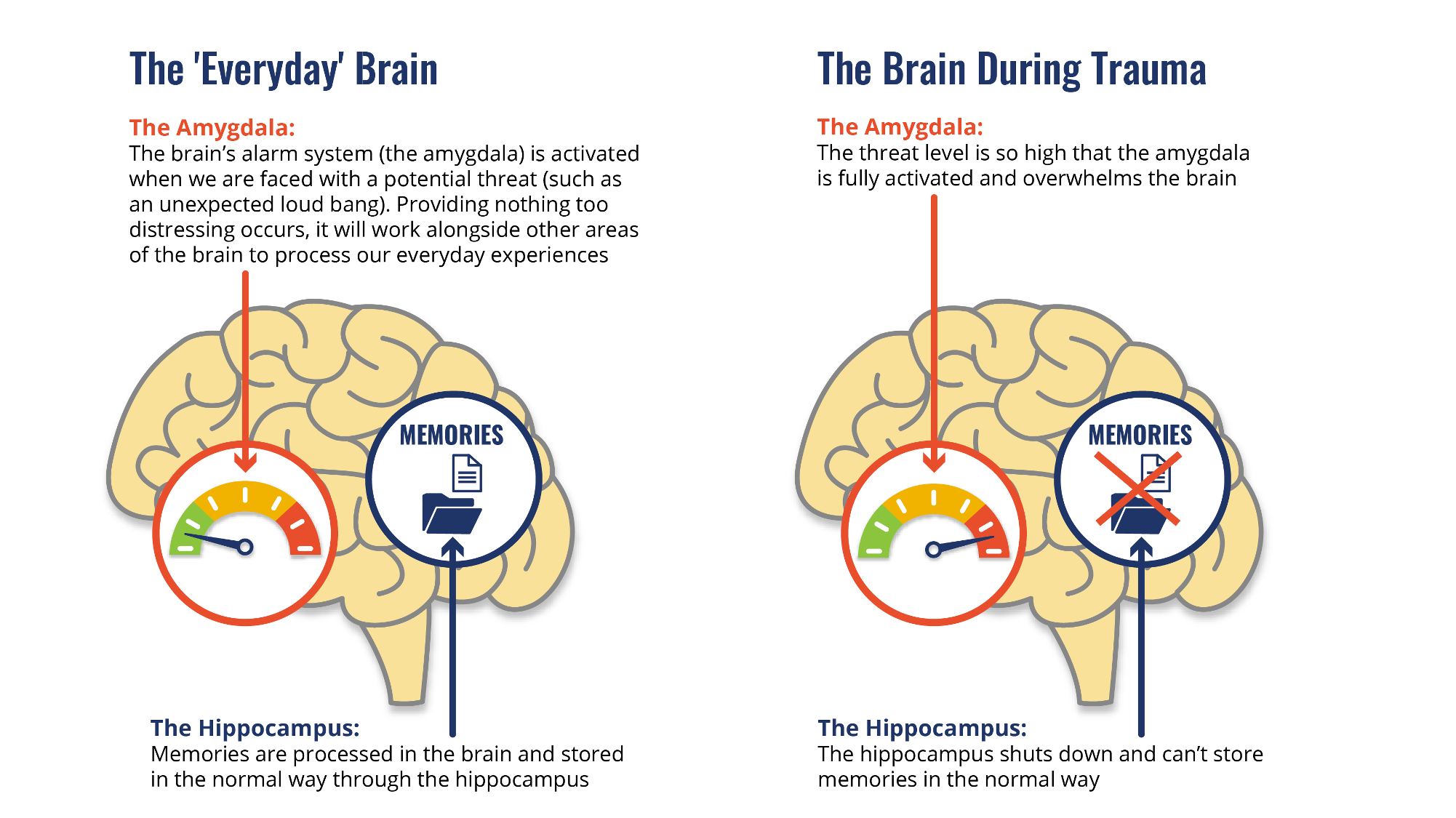

To help us think about trauma, its helpful to start with two areas in the brain which the picture below shows:

-

The hippocampus is all about accuracy and discrimination. This is what tells me that the bulge in your pocket is a mobile phone and not a gun. But in PTSD, the hippocampus becomes shut down and poor at discriminating. Every bulge is a gun, every dark shadow could contain danger. We need to reawaken the hippocampus and bring back discrimination.

-

The amygdala has become overactive and contributes to the adrenalin response. It's almost as though it has short circuited the hippocampus. The brain is stuck on 'fight-flight-fright' mode. We need to cool down the amygdala before we can do much else.

Medication can be helpful for the core symptoms but also for any associated depression. SSRIs, the main group of antidepressants, work. They are obviously not reprocessing the actual memory – they are a tablet so how could they do that?! But they do help with the symptoms. Also, there are medications that we know that seem to act on adrenaline – medications like doxazosin initially designed to treat blood pressure can do this.

Some doctors will recommend antipsychotics which can also do this, but these need to be used very sparingly because it is not psychosis or schizophrenia bein treated. However, in PTSD we do have something similar - unbidden things coming into the conscious mind – and so these medicines do seem to help a bit. Also, there's quite a strong overlap between trauma and psychosis. We know a lot of people with schizophrenia have a history of trauma, so piecing apart what is psychosis and what is a flashback can be quite difficult and you often see some confusion there.

Therapy is the other main approach. You might like to think of it like this - if the medication is turning down the amygdala, then we need to ask how do we stop the amygdala lighting up again and re-awaken the hippocampus. Well, this is what therapy does by reprocessing memories. Cognitive behavioural therapy is the main model here, and it's really important that you are working with someone who knows what they are doing with trauma focused CBT because it's quite a different approach to CBT for depression or anxiety. It is a longer course of therapy, and the sessions themselves are longer at times – to allow full reprocessing. You want a good and experienced trauma therapist - its worth the wait and maybe the cost to work with someone well-equipped.

Here are a couple of analogies to think about what is happening in the CBT.

The Duvet:

Think about trying to put a duvet away for the winter. If you just shove that duvet into the cupboard, the duvet usually doesn't go fully in. It sticks out and stops the door from shutting fully, and the door is slightly ajar with the duvet corner poking out. Every time you walk past, you bump into the door and the duvet shouts ‘hello’ to annoy you! This is a bit like what happens when we try and shove our memories away out of sight and repress them. They are going to keep pushing out until we do something with them.

We all know how to get the duvet in the cupboard. We have to get it out, spread it out on the bed, fold it up, roll it up and slide it correctly into the cupboard, and then you can shut the door. So this is what must happen with memories. They are still surrounded by all their emotion, and if they don't get filed away correctly they poke out - unless we get them out, strip away some of the emotion, fold them up correctly and put them away properly in the filing system. Then they will always be there as a memory because the trauma did actually happen, but the aim is to get to the point where the door can be shut and YOU can decide when you open the cupboard door – not the duvet!

The Factory:

Another analogy is what's called the factory analogy. Imagine that you're running a big processing plant and you've got lorries delivering the raw materials (which are the memories) into the loading bay. You want to put it on a conveyor belt so it can be taken off down to some distant part of the factory and stored away on a shelf. But the problem is, it's a massive great memory. Whenever you put it on the conveyor belt, it keeps falling off. It’s like the memory is in the middle of all this bubble wrap – and what you need to do is unwrap it, take all the packaging off, and then you're left with the memory that CAN go on the conveyor belt to the end of the factory, and be shelved away so you can access it when YOU want to.

Discussing PTSD treatments wouldn’t be complete with out mentioning EMDR - eye movement de-sensitisation and reprocessing, which is an odd-sounding technique where you watch a light move to and fro and can help with the re-processing – helping prepare you for it, enable you to stay a bit more calm, and help it to happen more quickly. Most recently in the pandemic, we even found that EMDR works fine over a video link!

Prevention

This is an area where the church can really help - in promoting good, healthy childhood experiences that will build resilience. Going away to two summer camps where you are taking part in life-changing adventures like managing to abseil down that wall or feel accepted into a group for the first time.

The church also has a key role in early support – straight after any trauma but before any therapy starts. You can’t diagnose PTSD immediately as the symptoms are also part of the normal brain response in the first few weeks, but you can still offer support.

Rob Waller, 26/04/2022