Mindfulness and CBT

This article was first published in Accord, the magazine of the Association of Christian Counsellors, and is reproduced here by kind permission of ACC and the authors.

The ‘third wave’ of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) – Can it be integrated into a Christian context?

By Sarah Plum and Paul Hebblethwaite

The theme of next year’s Association of Christian Counsellors conference in January 2011 is crossing the causeway and how counselling is changing and evolving. Throughout our lives we are constantly changing and developing as we encounter new experiences. Change is therefore not something to be feared but rather embraced. Indeed counselling is all about facilitating the client in change.

The aim of the article is to look at the possibility using Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy as a tool for treating depression and some forms of anxiety and how this may be compatible with Biblical teaching. We appreciate that some individuals may find this technique not compatible with their Christian faith, but we are not asking or expecting individuals to change their fundamental Christian beliefs or to participate in any practice that would contradict their faith but rather to look at how this tool can be used for the benefit of their clients. This article should be useful even to those that could not embrace this technique as it will at least give some useful insight.

The First and Second Waves of CBT

After the Second World War the first wave of the empirically based cognitive behavioural therapies was developed, to help combat the anxiety and depression following the war: this was termed behavioural therapy. In the 1950’s Ellis introduced the first approaches to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in his development of Relational Emotive Therapy, which was followed in the 1960’s by the empirical study of how thoughts (cognitions) effected emotion and behaviour. This was referred to as the ‘second wave’ or the ‘cognitive revolution’. This second wave was largely developed by A. T. Beck, and initially this approach was mainly applied to depression (Beck 1967), but was later developed to encompass anxiety in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and in the 1990’s taken further to cover couples work, personality disorders and substance abuse (Wills 2009). The second wave was also strengthened by Beck’s team, who helped to conceptualise and model therapy for a large number of disorders (see Wells 1997, and many others). A further development of the second wave was the introduction of Schema Focused Therapy (Young et al. 2003) in the 1990’s.

The Third Wave

The most recent change in CBT has been the introduction of the ‘third wave’, which examines whether trying to control our thoughts or emotions is part of the solution, or actually, part of the problem. This has led to the development of a process whereby we don’t just try to change what we think, but how we think. Many of the third wave therapies have a decreased emphasis on controlling our thoughts and emotions, and rather an acceptance of how they are, and changing how we react to them. The main third wave therapies include: Acceptance and Commitment Theory (ACT), Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), Behavioural Activation (BA), Functional Analytic Psychotherapy (FAP), Cognitive Behavioural Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP), and Integrative Couple Therapy (ICT). This article will concentrate on Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, some of the other approaches may be tackled in future articles.

Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

MBCT involves accepting thoughts and feelings without judgement rather than trying to push them out of consciousness, with a goal of correcting cognitive distortions (Segal et al 2002). Wills (2009) states that such a way of thinking stresses acceptance of the idea that thoughts and beliefs are mental events and processes rather than reflections of objective truths. It is recognised that some more fundamental Christians may feel uneasy with this later statement, as it may suggest that all thoughts and beliefs are transitory reflections that do not have any definite relationship with objective truth. For fundamentalists God’s Word is the objective truth and it is the Christian’s duty to submit all thoughts and feelings to it. Nevertheless, these ideas have been used highly successfully in the development of MBCT to prevent relapse of depression in clients and Christians will need to carefully evaluate their stance. In doing so the reader might consider that this form of therapy is utilised to try to combat recurring and paralysing sentiments and thoughts, and to reinforce the process of repentance, recognising that it is usually a process rather than an instant change. A further aspect of MBCT is the inclusion of our body as well as our emotions and thoughts. Williams et al (2009) point out that one area we often take for granted, whether depressed on not, is the body itself and the sensations within the body. Yet these sensations give us immediate feedback on our emotional and mental state and are therefore important to look at. The Bible informs us to look after our body as a temple for God and the Holy Spirit (Romans 12:1 and 1 Corinthians 6:19). So by attending to our body as well as our mind we will be honouring God.

Recent research is looking at treating patients who have recovered from 3 or more bouts of depression to see whether utilising mindfulness will help prevent relapse. In programmes devised in the Stay Well Programme (http://www.staying-well.org/ and http://stayingwell.bangor.ac.uk), patients learn the practice of mindfulness meditation and develop an awareness of the present moment, including getting in touch with moment-to-moment changes in the mind and the body. They also include basic education about depression and suicidal thoughts, and several exercises from cognitive therapy that show the links between thinking and feeling and how best to look after yourself when your moods threaten to overwhelm you. These programmes usually consist of eight-weekly two hour classes with weekly assignments to be done outside of the sessions.

This acceptance of our thoughts and emotions can be perceived as incompatible with the Christian faith as it appears to stem from the eastern traditions and religions (mainly Buddhism), but within the Christian tradition this could be referred to as living in the present moment and paying attention. This article examines whether it is possible to be mindful and pay attention in our day to day lives and counselling practice in a Christian context.

On closer examination of mindfulness it can be seen to be based on living in the present moment, and not in the past or the future, but in the here and now, (Kabat-Zinn 2009) and this could be seen to be in line with much of the teaching within the Bible. In Matthew 6: 34 we are instructed by Jesus to ‘Give your attention to what God is doing right now, and don’t get worked up about what may or may not happen tomorrow. God will help you deal with whatever hard things come up when the time comes’ (The Message). Consistent and complementary with this is the fact that the Bible encourages us to recognise the need for a decisive break with the past and to live in the light of who we are now in Christ with an eye on the end goal which is to be transformed into the likeness of his son.

Mindful Meditation

Much of mindfulness practice is based on meditation, and awareness of oneself (body, mind and spirit) and of the surrounding environment. The bible has many references to people meditating and meditation. However, there may be further difficulties for some Christians as Christian meditation is mainly centred on God, Christ, creation and scripture and rarely centred on self. The meaning and content of these Bible verses varies and includes our ultimate hope in God, His justice, love, righteousness, sustaining, wonders and works, the word, personal involvement with creation and the brevity of life. Psalm 143:5 states, ‘I remember the days of long ago; I meditate on all your works and consider what your hands have done’. Most of these examples are about filling the mind with good things including the truth about God, ourselves, his grace and purposes especially as they relate to his active involvement in our lives. The Apostle Paul sums this up in Philippians 4:8, ‘Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable--if anything is excellent or praiseworthy--think about such things.’ The self awareness part perhaps can be more easily accepted as it is a closer biblical concept to mindfulness than meditation. Many verses in Scripture talk about the Lords examination of us (see Psalm 139). Self awareness can be about understanding how God thinks about us as he examines us and also as he moves out in grace towards us based on what Christ has done for us. Another way of viewing meditation is that it is paying attention; this is often misunderstood as being self-centred or creating your own private spirituality. But by paying attention to your deepest self you are paying attention to God and you are paying attention to your neighbour (Freeman 2001).

Healing

What are the characteristics of mindfulness which enable healing to take place? Part of what is required is accepting that we are not in control and allowing things to be as they are. More specifically, you are admitting that things may need to change but that you are allowing God to change things in his own time. Far too often we try to control all aspects of our life. In mindfulness as well as in our Christian lives we have to learn to relinquish control. In our life as Christians this means observing and accepting things as they are and not constantly trying to change things to be as we would want. However, we need to guard against fatalism (what will be will be) as opposed to accepting God’s sovereignty but seeking to co-operate actively with God in response to his sovereign ordering of our lives such that we are best able to glorify him in our thoughts, feelings and actions. Fatalism leads to passivity with respect to our thoughts, feelings and actions but a healthy doctrine of God’s sovereignty leads to active partnership in seeking to move forward together with God according to His purposes. We are seeking in partnership with God to change things not as we want but as He wills (Romans 12:1).

The Major Pillars

There are seven attitudinal factors that constitute the major pillars of mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn 2009): non-judging, patience, a beginners mind, trust, non-striving, acceptance and letting-go. These pillars can also be seen as a good way to develop our Christian faith and by practising these (making every effort, Philippians 3:12-16; Colossians 1:29) we would not only be aiding our healing through mindfulness, but we could also draw closer to God.

1. Non-judging

The first of the pillars is to be non-judging. In mindfulness the aim is develop a stance of impartial witness to our experiences, and then to learn not to judge them but to accept them as they are. For it is when we make judgements that we cause stress within ourselves; for example by labelling someone or something as good or bad, interesting or boring, its working or not working. When we look at the Bible (Luke 6:36-38), it tells us that only God can judge us or others, and therefore the practice of being non-judging has a Biblical grounding. But Biblical counsellors may argue that the first role of a counsellor is to directly confront obvious or confessed transgression and it is accepted that this may be necessary in some cases (see Mathew 5:27-30). For instance someone battling with pornography should not accept it non-judgementally and utilise MBCT to avoid true guilt and Christian counsellors should not recommend they do so. MBCT is not recommended as a cure to sinful behaviour but for long term depression and some anxiety disorders that are not necessarily related to sinful behaviour. We need to be mindful that being sinful is not part of God’s plan for us and there needs to be a balanced Biblical awareness of this (Romans 12:1-2; Galatians 6:4; 1 Thessalonians 5:21) as there is a significant difference between being judging and making mature judgements about ourselves and sometimes others.

2. Patience

Secondly, patience is developed in mindfulness and demonstrates to us that we need to understand and accept the fact that sometimes things must unfold in their own time. As Christians we will often find ourselves wanting to rush God along to get to where we want to get to, but the Bible clearly teaches that we should wait on Gods timing and have patience (James 5:7, 9-11). I waited patiently for the Lord; he turned to me and heard my cry. He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire; he set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand. He put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and fear and put their trust in the Lord (Psalm 40:1-3). Kabat-Zinn (2009) likens patience and wisdom to waiting for a butterfly to emerge from its chrysalis in its own good time and that if we rush through life always striving for the next ‘better’ step we will miss the here and now. Indeed if we rush through life not living in the present we will undoubtedly miss many opportunities to serve God, by being too busy to notice the small things happening around us now. An example of this is the story of Martha and Mary in Luke 10:38-42. Patience means accepting that God has a plan and it will, like the butterfly, unfold in its own time. Understanding God’s patience with us can be a great help in understanding the need to be patient with ourselves.

3. Beginner’s mind

The third attribute is the beginner’s mind. This is about experiencing the richness of the present moment as it is, too often we take for granted the ordinary and fail to grasp the extraordinariness of the ordinary (Kabat-Zinn 2009). If we develop our sense of seeing everything as if for the first time we will truly be living and seeing Gods creation in all its glory. With our friends and neighbours we all too often don’t see them as they truly are, but by taking time to see them properly and how they are in this moment, we will be able to better respond to them and reflect some of God’s love onto them. This does not mean that we cannot accept that their past experiences may have moulded how they are in the present. Accepting them in the moment may enable them to trust us with their past. Part of the beginners mind is how we can appreciate Gods creation; the sky, stars, oceans, mountains, trees, and flowers as they are. If our mind is not focused on the here and now but worrying about the past or the future then we will not be able to do this effectively. Maybe Jesus’ command to be as little children fits well into this concept.

4. Trust

Learning to trust yourself and your feelings is also a part of the practice of mindfulness, particularly when God gives Biblical instinct to you as a believer. Fundamentalists may counter this by referring to Jeremiah 17: 1-9. However, this is not to say that we should only trust in ourselves, ultimately as Christians we trust in God (Proverbs 3:4-6; 4:5; 28:25-27). But God created us the way we are and with all our perceived faults and failings, He knows all our thoughts (Psalm 139) so learning to trust ourselves and God run hand in hand.When we practice meditation as Christians our aim is to develop a closer relationship with God. As we make this journey we will need to trust that we are hearing God correctly and to trust our faith in the presence of God that we are developing in these quiet times. As Christians we are testing everything we feel and not necessarily trusting everything we feel (Thessalonians 5: 21).

5. Non-striving

The fifth attribute is that of non-striving which can be a difficult issue. Some Christian teachers urge non-striving, (therefore ‘let go and let God or don’t wrestle, just nestle’) while others reject it. Paul says, ‘Not that I have already obtained all this, or have already been made perfect, but I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me (Philippians 3:12)’ and often uses analogies of the spiritual athlete. It is necessary, therefore, to draw a strong line between non-striving and spiritual apathy. If God is the aim, then a good case can be made for the later attitude. In life we tend to always do things for a reason, to reach a goal. But in meditation there are no goals except to be you and as Christians to be ourselves with God, and that we may have to rely totally on God to achieve this (2 Corinthians 3:18). Sometimes it will be hard to relax and just be with God, but we should learn to accept ourselves as we are as God accepts us by faith and not works (Ephesians 2:8). So if we are worried or anxious when we meditate we should accept that is how we are at that moment and give our concerns and worries to God, to accept them and not judge them. God wants us to cast our anxiety on him whether it is sinful or healthy anxiety (1 Peter 5:7).

6. Acceptance

Acceptance of ourselves, our situations and others means seeing things as they are in the present. All too often in today’s society we wish we were thinner, taller, richer, more assertive and we spend time condemning ourselves for not being as we would wish. But by accepting yourself as you are now is acknowledging that this is how God sees you and that he loves you as you are. When you accept yourself as you truly are then you will be able to make choices and changes. By cultivating acceptance you create the preconditions for healing (Kabat-Zinn, 2009). By accepting who and where we are in our lives and the things around us, doesn’t mean that you should not try to change things or that you should throw away your morals and standards. It just puts you in a true place from which to make changes and grow. This in Christian terms means that we can build on where we are and change things in order to move closer to God and grow more in the likeness of Christ.

7. Letting go

The final pillar of mindfulness practice is that of letting go (this can include forgiveness). Often we find it difficult to ‘just let go’ of certain thoughts, feelings or situations. With meditation and acceptance we practice seeing things as they are and develop the skill of just watching our thoughts whether good or bad and letting go of them. As Christians we need to learn through meditation and acceptance to identify these thoughts and concerns and then we can take them to God in prayerful meditation and put them at the foot of the cross. In Matthew 6:25-36 we are told to not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own. Furthermore, forgiveness is very much part of the Christian faith (Ephesians 4: 32; Matthew 6: 12; Luke 11:14; Mark 11:25) and Jesus tells us that, ‘if you forgive men when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their sins, your father will not forgive your sins (Matthew 6: 14-15).’

A Model for Mindfulness

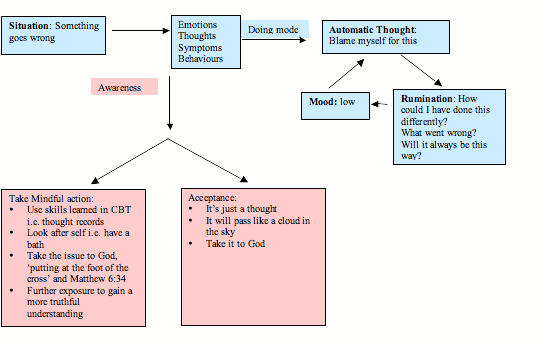

What does it actually mean to live in the present moment and how does this affect our moods and lives? If a life situation occurs that results in a significant change in emotion (affect) the client can prevent this spiralling into anxiety or depression by first becoming aware of what has happened and how they are reacting. Often in our busy doing problem solving mode of living that has evolved to try to escape from difficult situations we work on automatic pilot (Williams et al 2007). But unfortunately this problem solving mode often doesn’t work for our internal emotional issues. By paying mindful attention to thoughts and emotions we are able to see the affect that the situation has had on us and then in full awareness we can make one of the following two choices about how to react to them (Fig. 1).

1. Let them be, i.e. notice the thoughts and accept them as just thoughts.

2. Choose to act and change the thoughts and/or care for self.

Fig 1. Schematic representation of how we can deal mindfully with situations; where blue is the normal process and pink represents a change in the way of doing things.

Reflections

It will be up to individuals to look at MBCT and reflect how they use this approach, if indeed they use this approach at all. But utilising it as a tool to help clients overcome their depression or anxieties has been shown to be effective and we suggest closer examination by Christian counsellors.

As with all things in today’s world there may be perceived conflicts with our already busy lives as practicing mindfulness will take commitment and self discipline. But as Christian counsellors we could choose to learn these new skills, not just to help our clients but to benefit our health, and more importantly as a way of developing a closer relationship with God , our neighbours and our clients.

Feedback

We would greatly value your opinions (positive and negative) and any experiences you may have of MBCT, so please email any comments and thoughts to sara.plum1@btinternet.com. Sarah will be leading a workshop at the next ACC conference in January 2011 with the title: The ‘third wave’ of CBT – can it be integrated into a Christian context?

The Authors

Sarah Plum is a Trainee Cognitive Behavioural Therapist with special interest in the 3rd Wave.

Paul Hebblethwaite is a Christian Cognitive Behavioural Therapist with over 20 years of counselling training and experience.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help and constructive criticisms on this article from Dr John Hebblethwaite, the Rev. Peter Cousins, Harry Harmens and Judy Stammers, some of which has been incorporated in the final version.

References

Beck, A.T. 1967. Depression; clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York, Harper & Row.

Freeman, L. 2001. Excerpts from talk in Singapore. The World Community for Christian Meditation.

Kabat-Zinn, J. 2009. Full catastrophe living. Piatkus Books Ltd.

Segal, Z., Teasdale, J., Williams, M. 2002. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Wells, A. 1997. Cognitive therapy of anxiety. A practical guide. Chichester: Wiley.

Williams, M., Teasdale, J., Segal, Z., Kabat-Zinn, J. 2007. The Mindful way through depression. Guilford Press.

Wills, F. 2009. Beck’s cognitive therapy. Routledge.

Young, J., Klosko, S., Weishaar, M. 2003. Schema therapy – A practitioner’s guide. London: Guilford Press.

Sarah Plum, 03/12/2013